Behind The Pearl—the Planned Med School Site and Hallowed Ground for Charlotte’s Black Community

The Pearl, Atrium Health’s planned innovation district and home to Charlotte’s first medical school, will serve as a hub for the city’s future. How will it reckon with the painful history it’s built on?

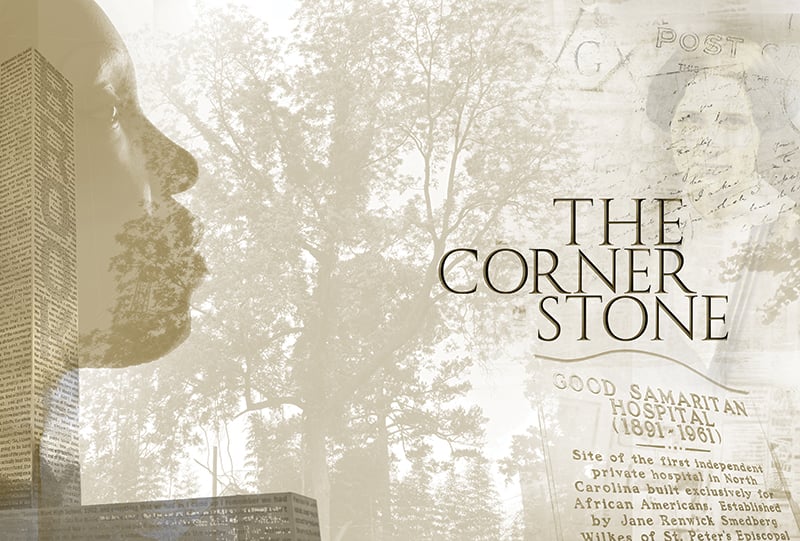

On Dec. 18, 1888, just 23 years after Appomattox, a crowd of Black and white Charlotteans gathered at St. Michael’s Chapel uptown. Led by clergy and members of the Masonic Fraternity, the jubilant band of citizens marched to 411 W. Hill St. in Third Ward. There, in a ceremony The Charlotte Observer called “mystic” and “impressive,” the Masons laid the cornerstone of the Good Samaritan Hospital.

They stuffed it with mementoes—among them the Book of Common Prayer, the previous day’s newspaper, and illustrated sketches of Charlotte—and consecrated the stone with “the Corn of Nourishment, the Wine of Joy, and the Oil of Plenty.” The ceremony closed with a series of speeches. The Rev. Wyche and the Rev. Tyler dwelled on the power of charity, “which overcometh all things.” The Rev. Mattoon, president of Biddle College, asked God to bless the endeavor.

Jane Renwick Smedberg Wilkes led fundraising to build Good Samaritan Hospital in uptown’s Third Ward, where Bank of America Stadium sits today.

With or without God’s help, the hospital faced a daunting prospect. Just laying the cornerstone was a momentous feat. The hospital was a project of St. Peter’s Episcopal Church, which had already opened the first civilian hospital in North Carolina. Parishioners wanted to build on that success with a hospital for Black residents. Charlotte philanthropist Jane Renwick Smedberg Wilkes wrote to every Episcopal diocese in the country for support. She begged her family to join the cause, so relentlessly that one brother asked her to stop. But by 1887, they’d raised enough. Good Samaritan Hospital, the first privately funded Black hospital in the state, opened in September 1891.

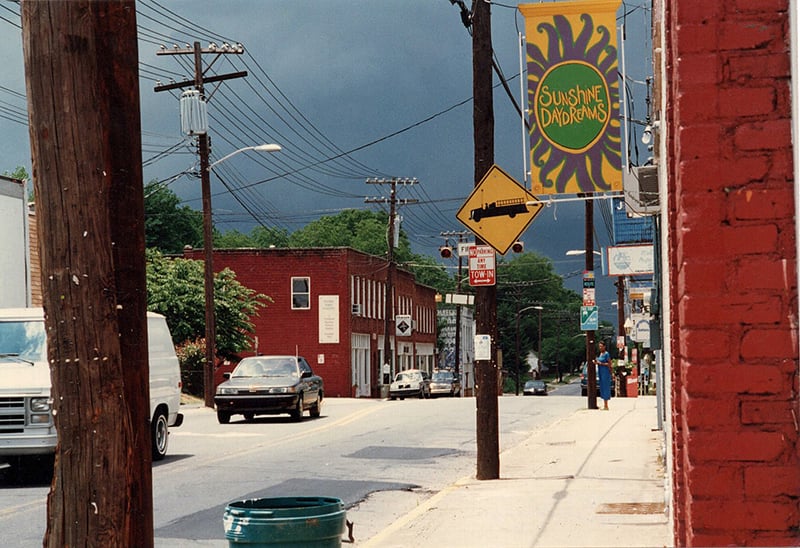

In March, 131 years later, Atrium Health referred to the hospital when it announced plans for The Pearl, an “innovation district” that will be anchored by the four-year Wake Forest University School of Medicine—another Charlotte first—when it opens in 2024. The district, which breaks ground this year, will sit at the intersection of Baxter and McDowell streets in what’s now known as midtown and what was once Brooklyn, a Black community demolished during the urban renewal era of the 1960s and ’70s. The Pearl takes its name from Pearl Street Park, one of Brooklyn’s few physical remnants.

The hospital’s nursing school trained hundreds of young women (above) to join a prestigious profession. Courtesy Robinson-Spangler Carolina Room, Charlotte Mecklenburg Library.

Between its fraught location and forward-looking mission, the mixed-use development will also occupy the sensitive intersection where Charlotte’s bulldozed past and glittering future meet.

Between its fraught location and forward-looking mission, the mixed-use development will also occupy the sensitive intersection where Charlotte’s bulldozed past and glittering future meet.

“In the South, historically, we often try to deal with the past by putting up something new,” says Jeffrey B. Leak, a professor of English and director of the American studies program at UNC Charlotte. “And new doesn’t erase what preceded it.” Leak wrote about his parents’ history in Brooklyn for this magazine in 2014. Now, he wonders, “In what substantive ways will this new creation speak to what was lost? To what was stolen?”

In Atrium’s announcement, President and CEO Eugene Woods, who is Black, tried to answer that question. “Many might say this area of town and its rich history have been largely overlooked,” he said. “But we’re here now to begin a new chapter to this story and honor this special place as we empower the neighborhoods around it, which are shaped by diverse people and perspectives, rooted in inclusivity and belonging, and filled with endless potential.” As in 1888, leaders today rightfully celebrate a shimmering future—and delicately dance around the realities that make their vision so hard to achieve.

***

Good Samaritan, too, was rooted in belonging, but racism immediately hampered its potential. The hospital depended on donations for blankets and basic supplies. It had no pathology lab or X-ray facilities, and the lack of these fundamental diagnostic tools hampered doctors’ and nurses’ ability to practice medicine. But at least they could practice medicine.

“I knew some older Black people who worked at Good Samaritan, and I heard those stories about how that was the only place a Black nurse could go and be a Black nurse,” Leak says, and one of the only places where Black patients were treated with dignity. In an echo of the future, the hospital established a nursing school in 1903 to boost young women into a respectable career.

“Good Sam” became a proud pillar in the community. Some Charlotteans still boast that they were born there. But its challenges never let up, and its eventual decline coincided with the civil rights movement. On Jan. 5, 1960, the Observer ran a story that outlined the NAACP’s opposition to some parts of the “slum clearance” plan that would wipe out Brooklyn. Leaders “called for more information about relocation housing for families that will be displaced” and “expressed fear that the program might lead to continued discrimination and segregation in housing.” On the same page, another story outlined Good Samaritan’s uncertain fate, as staff at Memorial Hospital—which would later become Carolinas Medical Center—vehemently opposed a $1.4 million-dollar plan to expand and improve Good Sam’s facilities.

Three months later, Ruthie Samuel, an indignant reader, wrote to the editor to excoriate the paper for its coverage. “It has been stated that white supervision is what’s needed to establish competency. Is one’s complexion to determine whether he is adequate or inadequate, and all other sources ignored?” she wrote. “Incidentally, white supervision is precisely what Good Samaritan has its share of.”

As Leak says now, “So often, the group that’s been kept out is expected to offer and provide all the answers to a problem that they didn’t create.”

***

But the civil rights movement made unlikely allies of those who wanted to shut the hospital down for incompetence and Black community members who themselves rallied to close it. They knew separate wasn’t equal and believed that integration held more promise than the plan to keep the ailing hospital on life support. In 1961, the city bought the hospital for $1 and integrated it as part of Charlotte Memorial Hospital.

“So often, the group that’s been kept out is expected to offer and provide all the answers to a problem that they didn’t create.” — Jeffrey B. Leak. Photo by Herman Nicholson.

Sixty years later, Memorial’s successor—the enormous Atrium Health conglomerate, Charlotte’s biggest employer—is still trying to make good on the promise of integration. The organization has six groups, councils, and committees dedicated to diversity, inclusion, and cultural competence. Their employee resources include a racial justice toolkit. They’ve also committed to diversifying their suppliers to include more minority-owned, woman-owned, and veteran-owned vendors. In 2018, BlackDoctor.org named Atrium one of its top hospitals for diversity.

The commitment to equity extends, in theory, to The Pearl. It’s a place where, Atrium says, “people from all walks of life will feel welcome.” The complex, which will include medical school facilities along with retail, apartments, a hotel, and community space, is expected to create 5,500 on-site jobs in the next 15 years, and a little less than half won’t require a college degree.

But late last year, nearby residents raised concerns about potential displacement. The district site borders Cherry, a historically Black neighborhood, and Sylvia Bittle-Patton of the Cherry Community Organization urged City Council to include affordable housing and health care. “(Brooklyn’s destruction) may have been decades ago,” she told the Observer, “but for Charlotte’s Black community, the betrayal is still fresh in our minds. We must be intentional about righting this wrong.”

If all goes according to plan, The Pearl will catapult Charlotte into the future and reshape the region’s economy. The next generation of doctors will study there. It will be, according to Atrium, a “ground-zero for entrepreneurial activity, research, and development.”

Leak’s parents died many years ago, but he tries to imagine what they would think of The Pearl. “I think my parents, and people of their generation, would be excited about the future but also concerned about what it costs to pay for this future,” he says. “What are we giving up as a community to have the skyscrapers? What is the Cherry neighborhood giving up to have this medical school? Because something has already been sacrificed.”

Allison Braden is a contributing editor.

Top image credits: Courtesy Robinson-Spangler Carolina Room, Charlotte Mecklenburg Library (2); JFields (3); Shutterstock (2)