“Chile, what you crying for?” As Black girls, we are taught how to be stoic as a means of survival. Our parents and others do not often know what to do with some of our emotions. And society definitely does not know what to do with a Black woman who displays her emotions publicly. Even in adulthood, this is repeated. And for high-achieving Black women, the problem becomes acute. The further up the ladder we go, we are told, “Girl, never let them see you cry!” Crying becomes associated with weakness.

Suppressing our emotions is often encouraged in Black women as a means of control and, most poignantly, for perceived protection. When our bodies experience emotions, those feelings are delegitimized because some, in our intimate lives and beyond, become uncomfortable, as they do not know how to respond to our emotions. Consider, for example, that the “mammy,” a stereotypical image of Black womanhood, never showed emotions. Thus, instead of dealing with her discomfort, she’d rather say no to the emotion. This sets up a vicious cycle—young Black girls learn to link their feelings to negative responses from their caregivers and society at large, which can further compound shame about how we feel. Meanwhile, our intellect and our beauty get praised.

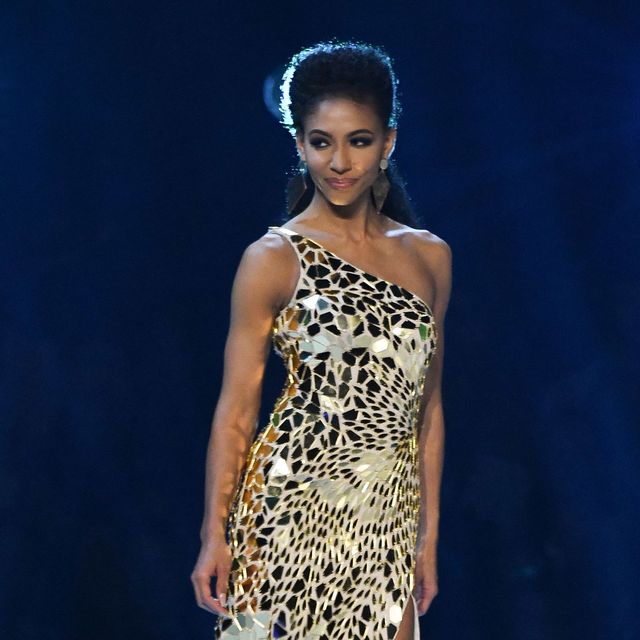

But what happens when we are consistently told not to cry? Where do those feelings go? The recent death of Cheslie Kryst, as a result of suicide, has brought Black women’s suicide front and center for the Black community and others. Generally, Black women do not die because of suicide. However, according to the CDC, in 2019 suicide was the second leading cause of death for Blacks or African Americans, ages 15 to 24.

Following her death, many reminisced of Kryst’s beauty, intellect, and care for her community. I found myself wondering, Was there space for her feeling body? The feeling body is that interior place of awareness that connects the mind, body, and spirit. It is that place of our truth. There are limited opportunities for Black women’s feeling bodies to enter public or even private spaces. This impacts Black women across all spectrums, but there is something peculiar related to high-achieving Black women who often receive the message not to share their feeling bodies.

Kryst’s mother, April Simpkins, informed the public that Kryst was suffering from “high-functioning depression” that she’d kept hidden. It is worth noting that high-functioning depression is not a clinically recognized diagnosis. It is a misconception that a clinically depressed person is “functioning” if they are employed, social, or generally appear to be participating in society. Kryst, like so many high-performing Black women, hid her feeling body because, as the late bell hooks told us, there is often very little space available for Black women to heal. hooks, in Sisters of the Yam, wrote, “Where are the spaces in our lives where we are able to acknowledge our pain and express grief?” With regard to our feeling bodies, we are taught and socialized at very young ages, not to show them. They become like the slip beneath a Sunday dress: present but not to be seen.

The feeling body of a high-achieving Black woman is often disappeared based, in part, on what I call The Jeffersons effect. The Jeffersons depicted the tales of a nouveau riche Black couple who had made it to the “deluxe apartment in the sky.” The Jeffersons effect suggests that once a Black woman has achieved her version of the deluxe apartment—a good job, et cetera—she is supernaturally able to overcome her feelings. When we do try to share or feelings, some , in both our intimate lives and outside, perceive us as “brats,” “complainers,” or as having “first-world problems.” We receive messages such as, “Your ancestors survived slavery. You have a better life, so what are you crying for?” Or we are told to “toughen up if we want to be successful.” What this then requires is a particular performance of Black womanness—one of stoic resilience and strength. Failure to adhere to this type of performance moves one outside the perceived boundaries of Blackness, for those both in- and outside the Black community.

Thus, we hold our feelings deep, often not sharing them with others who may see themselves as deeply connected to us. The Jeffersons effect means we live parallel lives where a particular type of intimacy is denied. Our feeling body is delegitimized as it challenges the boundaries of Black womanness, which sometimes demands that one be in total control of every aspect of one’s life. So when we experience sadness or depression, we begin to think that there is something internally wrong with us, that somehow, we are broken. After all, we are successful in other areas, so why can we not manage our emotions with the same level of success?

The result is that high-achieving Black women become disembodied—divorced from the reality of their emotions, denying the signals our own bodies send to us about our experiences. The solution to this problem begins with a simple question: Do I give high-achieving Black women space to cry?

Julia S. Jordan-Zachery is professor and chair of the Women's, Gender and Sexuality Studies Department at Wake Forest University. She is the author of many books, including most recently Black Girl Magic Beyond the Hashtag (Arizona University Press, 2019).