Abstract

The implementation of home-care robots is sometimes unsuccessful. This study aimed to explore factors explaining people’s willingness to use home-care robots, particularly among care recipients and caregivers. Surveys were conducted in Japan, Ireland, and Finland. The survey questionnaire comprised four categories (familiarity with robots, important points about home-care robots, functions expected from home-care robots, and ethically acceptable uses), with 48 items assessing users’ willingness to use home-care robots. The responses from 525 Japanese, 163 Irish, and 170 Finnish respondents were analyzed to identify common and distinct factors influencing their willingness to use these robots. Common factors across the countries included “willingness to participate in research and development,” “interest in robot-related news,” and “having a positive impression of robots”. The distinct factors for each country were: “convenience” in Japan; “notifying family members and support personnel when an unexpected change occurs in an older person” in Ireland; and “design” in Finland. Therefore, developers should determine potential users’ willingness to participate in the research and development of home-care robots and consider a system that involves them in the development process.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Population ageing is progressing at a rapid pace in developed countries. By 2060, older adults are expected to account for 28.2% of the total populations in Europe, North America, Japan, Australia, and New Zealand1. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that by 2030, one in six individuals globally will be aged 60 years or older2. This suggests that the number of family members and professionals available to provide care for older adults in their homes will be insufficient. The Japanese government reported that an additional 250,000 caregivers will be needed by 20263. Keva, a pension provider for public sector employees in Finland, estimated that there will be shortage of 16,600 nurses, including those caring for older people in 20224. Half of the shortage has occurred in the last two years. Family Carers Ireland found that about two-thirds of family carers felt they could not receive formal support because of inadequate staffing5.

Simple, reliable, and effective technologies are needed to mitigate the impact of care workforce shortage and help older adults to age in their homes6. One way to overcome this shortage is to develop and deploy “robot technology to help older adults become more independent and reduce the burden on caregivers”7. Considering the effective use of the limited workforce, the Japanese Government implemented several programs regarding care robots. In November 2012, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare and the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry formulated the “Priority Areas for the Use of Robotics in Long-Term Care,” which included home-care; it was revised in 20148. However, the development and sale of several highly anticipated care robots was discontinued because of difficulty in developing products that could meet the needs of Japanese long-term care settings9. This is not unique to Japan. Care robots were developed and widely touted in the media, but failed to sell in Finland too10. Gaining social acceptance for such assistive home-care robots remains a common issue in ageing societies11,12,13,14. Even with the support and recommendations of government agencies and technology developers, the use of care robots on an appropriate scale would be difficult to attain and sustain15.

Studies have shown that in spite of technological advancement in assistive technologies, the acceptance of robots among older adults remains low16,17,18,19. Recently, Maibaum et al.20, in their critique of care robots in healthcare, argued that “there has been a fundamental conflict between economic, professional, and ethical care concepts and that this care conflict shapes the phenomenon of care robots” (p. 470). The circumstances in which home-care robots are used vary according to users’ mental and physical conditions, home environment, and financial situation. These factors are related to the inner setting domain of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR), which assesses multiple factors influencing the implementation of innovations21,22. The current CFIR defines “recipient-centeredness,” focusing on the needs of the recipient (patient), as a concept similar to the “user-centric principle.” Given that the user of CFIR is the developer, what more specific considerations should they take into account?

Several components of user-centric principles have been addressed in previous studies on technology acceptance models23,24. Theoretical models explain the public’s technology acceptance. Some models, such as the Almere model (AM), determine user acceptance of social assistive robots for older adults23. To the best of our knowledge, Alaiad and Zhou24 were the first to introduce ethical concerns in the adoption of home healthcare robots, using a technology acceptance model (a structural model of determinants; SMD). They raised issues of privacy—referring to the lack of control over the collection and use of personal information—and ethical concerns—defined as a standard of behavior and a concept of right and wrong beyond legal concerns. A previous study elucidated the relationship between the willingness to use home-care robots and ethical issues, including personal information and privacy protection, which were similar to Alaiad and Zhou’s concept of privacy concerns25. Another component of the user-centric principle is the participation of the user in research and development26. Indeed, users’ willingness to participate in research and development can potentially encourage willingness to use home-care robots25. A systematic review showed that NIHR public involvement and engagement project (INVOLVE) in the UK facilitated public involvement in health care research, which had a positive impact on the enrolment of study participants27. INVOLVE had broad impacts such as improving research quality and design, fostering trust and empowerment among the public, and increasing awareness of the ethical and moral imperatives of researchers.

This study examined how much user-centric principles affect users’ willingness to use home-care robots, compared to other factors such as users’ attributes, past experience, and features and functions of the robots. Thus, first, this study aimed to explain the general structure of users’ willingness to use home-care robots. Second, it aimed to address whether the user-centric principles are fundamental and universal across countries. Therefore, we conducted surveys in Japan, Ireland, and Finland. Despite differences in population ageing rates among the three countries, we found common challenges related to population ageing; furthermore, all three countries have national strategies for ageing (Table 1).

Results

Demography of the respondents

A total of 1,004 potential users of home-care robots responded to the questionnaire: 528 from Japan, 296 from Ireland, and 180 from Finland. As willingness to use a home-care robot was the dependent variable for the analysis, responses that left the question item unanswered were excluded from the analysis. Consequently, data from 525 Japanese, 163 Irish, and 170 Finnish respondents were analyzed (Table 2).

Missing values were imputed by question items 2–14 for Japanese respondents, 2–25 for Irish respondents, and 1–16 for Finnish respondents Therefore, the number of respondents for whom data were imputed per question item ranged from 0.4 to 2.7% of the Japanese, 1.2–15.3% of the Irish, and 0.6–9.4% of the Finnish participants. By country, the largest difference in mean score for every item after imputation was ± 0.010 for Japan, ± 0.050 for Ireland, and ± 0.030 for Finland. The differences for the standard deviations were smaller: -0.010 for Japan, -0.063 for Ireland, and − 0.043 for Finland (Appendix Table 1).

Analysis

As there was no high correlation among the items based on correlation analyses, we included all items in the bivariate analysis. In the bivariate analysis for all three countries, many items—including all four items for ethically acceptable uses—were significantly associated with the willingness to use a home-care robot (Appendix Table 2). Significant items in all three countries were “I am interested in robot-related news” and “I have a positive impression of robots” for familiarity with robots, and “willingness to participate in research and development” for ethically acceptable uses (Appendix Table 3).

Multivariate regression analysis identified the items that predicted the willingness to use a robot (Table 3). Adjusted R2 were 0.381 to 0.531 and none of the relationships between the items had a VIF of 4 or greater. For ethically acceptable uses, the “willingness to participate in research and development” item was a significant factor in all three countries(Japan: 0.188[standard error (SE) = 0.033], Ireland: 0.222[SE = 0.055], Finland: 0.263 [SE = 0.053]), as were “I am interested in robot-related news” (Japan: 0.262[SE = 0.053], Ireland: 0.445[SE = 0.066], Finland: 0.212 [SE = 0.066]) and “I have a positive impression of robots” (Japan: 0.217[SE = 0.048], Ireland: 0.205[SE = 0.064], Finland: 0.319 [SE = 0.059]) for familiarity with robots.

Distinct items were the following. Japanese respondents’ willingness to use home-care robots were “convenience” for important points about robots; and “providing support for movement/mobility of older people in their daily lives” for functions expected from home-care robots. Irish individuals’ willingness to use these robots was influenced by the expectation that they would “notify family members and support personnel when an unexpected change occurs in an older person” for functions expected from home-care robots. The Finnish participants emphasized the importance of “design” when considering home-care robots (Table 3).

Discussion

This study explored the willingness to use home-care robots among potential users in Japan, Ireland and Finland. We found commonalities in the use of home-care robots that empirically support the concept of user-centric principles.

We sequentially discuss the implications of the results derived for the three countries. The final analysis for predicting the willingness to use a home-care robot in Japan included two items related to familiarity with robots: interest in robot-related news and having a positive impression of robots. Thus, in Japan, subjective aspects were identified as unique factors.

Home-care robot development in Japan is being encouraged by the government, industry, and academia, and robot-related marketing is being used to increase the demand for robots, according to robotic anthropology research28,29. In other words, rather than the Japanese being culturally pre-disposed to feeling amicable towards robots, the society strives to align its culture to become robot-friendly30. Compared to Western Europe, East Asia has always been viewed as being more inclined towards “techno-optimism”31. Consequently, government officials and the developers of home-care robots have the techno-optimistic belief that robots are the solution to home-care in an ageing society. Hence, in Japan, robot-related news may be designed to increase the demand for these robots because people with an interest in robot-related news are more susceptible to influence on this subject.

Lolich et al.32 state that Ireland is presently behind in its uptake of robotics in general. However, vigorous investment is expected to accelerate the uptake to bridge the digital divide. In 2021, the population ageing rate in Ireland was 14.8%33; it has increased by 35% since 2013, considerably higher than the EU average increase of 17.3%34. Given this unique situation, the finding that interest in robot-related news relates to willingness to use a home-care robot suggests a strong inclination of respondents towards home-care robots.

Several stakeholders in Ireland perceive healthcare policies, such as Sláintecare, as drivers embedding artificial intelligence and robotics into health and social care in the country35. In May 2021, the government published the Sláintecare Implementation Strategy and Action Plan 2021–23, which emphasized the role of technology and digital innovations to integrate care pathways. If successfully implemented, safe and timely access to care will be enabled for older people. In the past few years, there has been a significant emphasis on humanoid robots, such as Stevie and Mylo, that have been featured in domestic and foreign media. Thus, the expectations may reflect an overblown image of robots as popular, which contrasts with their low production and usage rates.

In Finland, “design” was associated with the willingness to use a home-care robot in the statistical analysis. Finnish design is well known globally and is important in robot manufacturing36. Additionally, the “capacity to increase mental and physical wellbeing and comfort” was a significant factor in logistic regression analysis. Finland has advanced information and communication technology (ICT) manufacturing, which uses robots for logistics37. Accordingly, a proposal entitled Robotics in Care Services: A Finnish Roadmap38—which cites the conceptual framework for dignity from a study of nursing home residents by Pleschberger39 —argues for the importance of interpersonal dignity when developing robots for use in care services. As for what should be considered when adopting a robot, Finnish respondents’ selection of “capacity to increase mental and physical wellbeing and comfort” reveals that they hold strong user-centered values, possibly because of this proposal.

Both the “ethically acceptable uses” and “familiarity with robots” were common factors across the three countries. For the first time, robots are being used to help in the health of humans40. Japan, Ireland, and Finland have different historical, cultural, demographic, and economic backgrounds. Our results demonstrated both commonality and unique aspects for each country. Unsurprisingly, familiarity with robots is an important factor. Although it is difficult to explain why user participation in the research and development process is a common factor, it is likely crucial for improving societal acceptance of home-care robots.

Therefore, a system that encourages participation in research and development of home-care robots is needed. Lolich et al.32 argue that the successful adoption of home-care technology requires an understanding of the user’s social position, from the economic, political, emotional, and cultural value perspectives. Pilotto et al.12 also suggest the significance of interdisciplinary collaboration by researchers, developers, and end-users to implement technologies aimed at meeting older people’s needs. To this end, conducting empirical studies would be more informative for the future. One study reported participants’ changes in understanding the robot through a year-long, seven stage co-design process with 28 older people41. A Finish study focused on conducting participatory research by using action research and living lab methodologies to develop and apply robots in care for older people42. Developers across countries should be aware of this significance and consider developing a system that involves potential users in the development process.

This study has some limitations. First, data were collected between November 2018 and February 2019. Since then, both people and society’s perceptions of robots and other technologies may have changed because of their experience with the COVID-19 pandemic. The environment surrounding home-care robots is likely to change due to emerging infectious diseases, aging populations, and developing technologies such as ICT and artificial intelligence. These changes must also be considered when conducting user-centric research and development. Second, other countries involved in the development and manufacture of robots, such as the U.S., China, and Germany, were not included in the study. Third, the number of survey participants in the three countries was not sufficient to analyze each demographic (older adults, family caregivers, or home-care professionals). Even if commonalities in the willingness to use home-care robots were found across countries, differences may exist because of these attributes. Finally, this study has a self-report bias because it describes the home-care robot briefly and presents images. Recent studies aimed at explaining the acceptability of care robots have used vignettes describing detailed use settings of the care robots43,44. Developing more-reliable methods for clarifying users’ perceptions of home-care robots remains a challenge.

Our findings indicate that potential users’ intention to participate in research and development processes was associated with their willingness to use home-care robots. However, not many people can actually participate in the research and development process. Therefore, it is necessary for developers to be more proactive in keeping user-centric principle in mind. In the future, the biggest challenge may be to create a system that involves older adults, family caregivers, and care professionals and develop home-care robots that users truly need in their daily lives, while considering the potential risks and benefits.

Methods

Survey

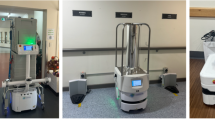

We developed a conceptual framework of factors that could potentially determine the willingness of users to use a home-care robot. In this framework, willingness to use a home-care robot (willingness to use one to care for a family member, for personal care, and for older adults) were determined by sex; age; experience with robots; ethical principles of respect for patient autonomy, non-maleficence, and beneficence; and features and functions of home-care robots to meet the needs of the older people. Details regarding the preparation of the survey questionnaire are described in Suwa et al.45 and Tsujimura et al.46. The survey questionnaire comprised four categories—familiarity with robots, important points about home-care robots, functions expected from home-care robots, and ethically acceptable uses, with a total of 48 items (Appendix Table 1). The questionnaire included typical images of robots alongside the definition (Fig. 1).

Images of home-care robots provided in the questionnaire.

The figure included typical images of robots. We presented the figure to the study subjects with the following definition of home-care robots in the questionnaire: “Home-care robots come in many forms. The term “home-care robot” used in this survey is a general expression for devices and systems that perform functions such as monitoring older people and their surroundings and providing support for older people and/or their caregivers (including communication that enables interactive conversation, assistance with activities of daily living, or managing medications).”

We conducted surveys in Japan, Ireland and Finland between November 2018 and February 2019. Details regarding the survey procedure are described in Suwa et al.47 and Kodate et al.48. A brief description of the survey procedure in each country is provided below.

Japan

The survey respondents were people aged 65 years and over, family caregivers, and home-care professionals in a prefecture. In 2018, the ageing rate in this prefecture was 28.1%, similar to the national average. We systematically sampled home-care offices from those listed in the government’s Long-Term Care Insurance service information disclosure system. We distributed the questionnaire to 1,936 older people, 2,652 family caregivers, and 1,073 home-care professionals. Those aged 65 years and over as well as family caregivers received the questionnaire forms from the home-care professionals. An online version of the questionnaire was also prepared, so the respondents could answer either by post or via the Internet.

Ireland

The responses were collated from three groups. Age Action Ireland distributed the questionnaire to their members (N = 1,154), who included people aged 65 years and over who were or might possibly be using health or social care services, and family caregivers who were or might possibly be using services related to nursing care. They completed the questionnaire and sent it back to the researchers. The Irish Gerontological Society (IGS) agreed to distribute the questionnaires to home-care/health and social care professionals, including nurses and care providers. An email including a link to an online version of the questionnaire was sent to the respondents, who answered the questionnaire via the Internet.

Finland

The respondents were potential users of home-care robots aged 65 years and over, family caregivers, and home-care professionals in two regions. The questionnaires were distributed by mail in cooperation with the municipal governments. We distributed 1,405 questionnaires. People aged 65 years and over and family caregivers completed the questionnaire and sent it back to the researchers, whereas the home-care professionals could answer the questionnaire either by post or via the Internet.

Data preparation

The survey items presented to the participants are shown in Appendix Table 1. Respondents were asked to rate their willingness to use a home-care robot if they were to begin receiving long-term care at home. We employed a 4-point Likert scale, rather than a 5-point one, to avoid “either” or “neither” responses, and to conduct further bivariate analysis (1: I would like to use one, 2: I would rather use one than not, 3: I would rather not use one, or 4: I would not want to use one). For the bivariate analysis, a binary variable “willingness to use a home-care robot” was created by converting ratings 1 and 2 into “1: yes” and ratings 3 and 4 into “0: no.”

For the independent variables, responses comprised four categories: familiarity with robots, important points about home-care robots, functions expected from home-care robots, and ethically acceptable uses. The questionnaire comprised 38 items in the following categories: familiarity with robots (How familiar are you with robots?; 7 items rated from 1: not at all to 4: very familiar), important points about home-care robots (To what extent do you place importance on the items below in regard to home-care robots?; 16 items rated from 1: not important to 4: important), and functions expected from home-care robots (To what extent do you think it would be useful for home-care robots to provide the types of support indicated below?; 15 items rated from 1: not expected to 4: expected). For the bivariate analysis, we converted the variables into binary variables by combining ratings 1 and 2 and ratings 3 and 4.

Confirmatory factor analysis based on a previous study confirmed that “ethically acceptable uses” had a 4-factor structure from 10 items (Rated from 1: unacceptable to 4: acceptable)25. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the four factors—acquisition of personal information, use of personal information for medical and long-term care, secondary use of personal information, and willingness to participate in research and development—were 0.755, 0.832, 0.887, and 0.844, respectively. We calculated the mean and quantile values for each of the four factors (collection of personal information, usage of personal information for medical or nursing care, usage of secondary personal information, and willingness to participate in research and development). These values were used as a threshold when we converted the variables into binary and quantile variables.

Analysis

We computed the descriptive statistics of the survey participants from the three countries. For the dependent and independent variables, we imputed missing values using the linear regression approach. Descriptive statistics were computed for each factor before and after imputation to verify that the means and standard deviations after imputation remained in close approximation. The descriptive statistics of the dependent and independent variables were compared across the three countries using the χ² test. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were calculated for each category by each country.

Factors associated with willingness to use a home-care robot for each country were identified in the following three stages. First, associations between willingness to use a home-care robot and the items were identified using the χ² test and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables, and t-test for continuous variables. Second, to identify significant items for each category, a logistic regression analysis with binary independent and binary dependent variables was performed after checking the correlations among the items. Finally, we conducted a multivariate regression analysis using a 4-point scale or quantile independent variables and a 4-point scale dependent variable. We tested for adverse effects from multicollinearity between the variables using the criterion of a variance inflation factor (VIF) of 4 or greater49; goodness of fit was tested using adjusted R2. The analyses were performed using SPSS version 28. The statistical significance level was set at 5%.

Ethical considerations

All study procedures were conducted in accordance with the guidelines and regulations of each institution and country. The study was reviewed and approved by the ethics review committees in each country: Chiba University Graduate School of Nursing Ethics Review Committee (No. 30-19) in Japan, University College Dublin’s Human Research Ethics Committee - Humanities (HS-18-81- KODATE) in Ireland, and the City of Seinäjoki and the Joint Municipal Authority of Ilmajoki and Kurikka (JIK), both in Finland. We provided a written explanation of the study in accordance with the guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was obtained from all respondents and/or their legal guardians before answering the questionnaire.

Data availability

Data are available from the authors upon reasonable request. Please contact the corresponding author (suwa-sayuri@faculty.chiba-u.jp).

References

Cabinet Office of Japan. Reiwa 4nen ban Kōrei Shakai Hakusho [Annual Report on the Ageing Society]. (2022). https://www8.cao.go.jp/kourei/whitepaper/w-2022/zenbun/pdf//1s1s_02.pdf

World Health Organization. UN decade of healthy ageing: Plan of action 2021–2030. (2020). https://www.who.int/initiatives/decade-of-healthy-ageing

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Kaigo jinzai kakuho ni muketa torikumi [Efforts to secure nursing care personnel]. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/newpage_02977.html) (n.d.).

Keva Kuntasektorin työvoima-ennuste [Local Government Sector Labor Force Forecast]. (2023). https://www.keva.fi/contentassets/de5752333bfb4e0a8194a8797ed24935/analyysi-kuntien-tyovoimatarpeista-2023.pdf

Family Carers Ireland. The State of Caring 2024. (2024). https://www.familycarers.ie/media/3549/family-carers-ireland-state-of-caring-2024.pdf

Hawley-Hague, H., Boulton, E., Hall, A., Pfeiffer, K. & Todd, C. Older adults’ perceptions of technologies aimed at falls prevention, detection or monitoring: a systematic review. Int. J. Med. Inf. 83 (6), 416–426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2014.03.002 (2014).

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Kaigo robotto no kaihatsu fukyu no sokushin [Promotion of the development and implementation of care robots]. (2018). https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/0000209634.html

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Robotto gijutsu no kaigoriyou niokeru jyutenbunya no kaitei [Revision of priority fields in long-term care]. (2014). https://www.mhlw.go.jp/seisakunitsuite/bunya/hukushi_kaigo/kaigo_koureisha/topics/tp140203-1.html

Mitsubishi Research Institute. Robot kaigokiki kaihatsu・hyoujunkano seika, kadai oyobi kongono jigyouuneini kakawaru bunseki houkokusho [Report on the results, issues, and future operation of the robot care equipment development and standardization project 2020]. (2020). https://www.amed.go.jp/content/000098807.pdf

Niemelä, M. et al. Robots and the future of welfare services – A Finnish roadmap. Aalto University publication series CROSSOVER. (2021). http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-64-0323-6

Granja, C., Janssen, W. & Johansen, M. A. Factors determining the success and failure of eHealth interventions: systematic review of the literature. J. Med. Internet Res. 20(5), e10235 (2018).

Pilotto, A., Boi, R. & Petermans, J. Technology in geriatrics. Age Ageing. 47 (6), 771–774. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afy026 (2018).

Schreiweis, B. et al. Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of eHealth services: systematic literature analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 21 (11), e14197. https://doi.org/10.2196/14197 (2019).

Yang, D. & Moody, L. Challenges and opportunities for use of smart materials in designing assistive technology products with, and for older adults. Fashion Pract. 14 (2), 242–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/17569370.2021.1938823 (2022).

Lupton, D. Critical perspectives on digital health technologies. Sociol. Compass. 8 (12), 1344–1359. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12226 (2014).

Laitinen, A., Niemelä, M. & Pirhonen, J. Social robotics, elderly care, and human dignity: a recognition-theoretical approach in What Social Robots can and should do (eds Seibt, J., Nørskov, M. & Andersen, S.) 155–163 (IOS, (2016).

Li, J., Ma, Q., Chan, A. H. & Man, S. Health monitoring through wearable technologies for older adults: Smart wearables acceptance model. Appl. Econ. 75, 162–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2018.10.006 (2019).

Rantanen, T., Lehto, P., Vuorinen, P. & Coco, K. The adoption of care robots in home care—A survey on the attitudes of Finnish home care personnel. J. Clin. Nurs. 27 (9–10), 1846–1859. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14355 (2018).

Turja, T. & Oksanen, A. Robot acceptance at work: a multilevel analysis based on 27 EU countries. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 11 (4), 679–689. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12369-019-00526-x (2019).

Maibaum, A., Bischof, A., Hergesell, J. & Lipp, B. A critique of robotics in health care. AI Soc. 37, 467–477. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-021-01206-z (2022).

Damschroder, L. J. et al. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement. Sci. 4, 50. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-4-50 (2009).

Damschroder, L. J., Reardon, C. M., Widerquist, M. A. O. & Lowery, J. The updated Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research based on user feedback. Implement. Sci. 17, 75. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-022-01245-0 (2022).

Heerink, M., Kröse, B., Evers, V. & Wielinga, B. Assessing acceptance of assistive social agent technology by older adults: the Almere model. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2 (4), 361–375. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12369-010-0068-5 (2010).

Alaiad, A. & Zhou, L. The determinants of home healthcare robots adoption: an empirical investigation. Int. J. Med. Inf. 83 (11), 825–840. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2014.07.003 (2014).

Ide, H. et al. Developing a model to explain users’ ethical perceptions regarding the use of care robots in home care: a cross-sectional study in Ireland, Finland, and Japan. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 116, 105137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2023.105137 (2024).

McWilliams, A. et al. Patient and family engagement in the design of a mobile health solution for pediatric asthma: development and feasibility study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 6 (3). https://doi.org/10.2196/mhealth.8849 (2018). e68.

Crocker, J. C. et al. Impact of patient and public involvement on enrolment and retention in clinical trials: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 363, k4738. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k4738 (2018).

Kovacic, M. The making of national robot history in Japan: Monozukuri, enculturation and cultural lineage of robots. Crit. Asian Stud. 50(4), 572–590 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1080/14672715.2018.1512003.

Vogt, G. & König, A. S. L. Robotic devices and ICT in long-term care in Japan: their potential and limitations from a workplace perspective. Contemp. Japan. 35 (2), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/18692729.2021.2015846 (2021).

Kureha, M. Nihonjin to Robot -techno-animism heno hihan [Japanese and robots - criticism of techno-animism theory]. Contemp. Appl. Philos. 13, 62–82. https://doi.org/10.14989/265441 (2021).

Kodate, N. et al. Hopes and fears regarding care robots: content analysis of newspapers in East Asia and Western Europe, 2001–2020. Front. Rehabil Sci. 3, 1019089. https://doi.org/10.3389/fresc.2022.1019089 (2022).

Lolich, L., Pirhonen, J., Turja, T. & Timonen, V. Technology in the home care of older people: views from Finland and Ireland. J. Cross-Cult Gerontol. 37 (2), 181–200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10823-022-09449-z (2022).

OECD. Elderly population. (2021). https://data.oecd.org/pop/elderly-population.htm#indicator-chart

Department of Health, Ireland. Health in Ireland key trends 2022. (2022). https://www.gov.ie/pdf/?file=https://assets.gov.ie/241598/8a6472b4-83cf-45ec-88c9-023e0c321d8c.pdf#page=null

Kodate, N., Mannan, H., Donnelly, S., Maeda, Y. & O’Shea, D. Can care robots support ageing in place in Ireland? Key stakeholders’ perspectives on enabling assistive technology and users’ quality of life in Elgar Handbook on Disability Policy (eds Fisher, K. & Robinson, S.) (Edward Elgar Publishing, (2023).

Iioka, M. Design in Finland: its nature and modernity. Kyushu Sangyo Univ. Res. Rep. Fac. Arts. 27, 62–70 (1996).

European Commission. Directive 2010/40/EU progress report. Finland. (2017). https://transport.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2018-06/2018_fi_its_progress_report_2017.pdf

ROSE Consortium. Robotics in care services: A Finnish roadmap. (2017). http://roseproject.aalto.fi/images/publications/Roadmap-final02062017.pdf

Pleschberger, S. Dignity and the challenge of dying in nursing homes: the residents’ view. Age Ageing. 36 (2), 197–202. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afl152 (2007).

Honda, Y. Nursing care robots. J. Rob. Soc. Japan. 38 (2), 159–161. https://doi.org/10.7210/jrsj.38.159 (2020).

Ostrowski, A. K., Zhang, J., Breazeal, C. & Park, H. W. Promising directions for human-robot interactions defined by older adults. Front. Robot AI. 11, 1289414. https://doi.org/10.3389/frobt.2024.1289414 (2024).

Lehto, P. Robots with and for the elderly people – case study based on action research. ICERI2017 Proc. 381–387. https://doi.org/10.21125/iceri.2017.0153 (2017).

AboJabel, H. & Ayalon, L. Attitudes of israelis toward family caregivers assisted by a robot in the delivery of care to older people: the roles of collectivism and individualism. Technol. Soc. 75, 102386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2023.102386 (2023).

Schönmann, M., Bodenschatz, A., Uhl, M. & Walkowitz, G. The care-dependent are less averse to care robots: an empirical comparison of attitudes. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 15, 1007–1024. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12369-023-01003-2 (2023).

Suwa, S. et al. Home-care professionals’ ethical perceptions of the development and use of home-care robots for older adults in Japan. Int. J. Hum. -Comput Interact. 36 (14), 1295–1303. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2020.1736809 (2020).

Tsujimura, M. et al. The essential needs for home-care robots in Japan. J. Enabling Technol. 14 (4), 201–210. https://doi.org/10.1108/JET-03-2020-0008 (2020).

Suwa, S. et al. Exploring perceptions toward home-care robots for older people in Finland, Ireland, and Japan: a comparative questionnaire study. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 91, 104178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2020.104178 (2020).

Kodate, N. et al. Home-care robots –attitudes and perceptions among older people, carers and care professionals in Ireland: a questionnaire study. Health Soc. Care Community. 30 (3), 1086–1096. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.13327 (2022).

Takiguchi, T. A review of oral epidemiological statistics, part III: interpretation of various goodness of fit indicators for the multiple regression model and multiple logistic regression model. Health Sci. Health Care. 5, 35–49 (2005).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the supporting organizations and participants of the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Hiroo Ide: Methodology, Analysis, Writing – original draft. Sayuri Suwa: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Funding acquisition. Yumi Akuta: Analysis, Writing – original draft. Naonori Kodate: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation. Mayuko Tsujimura: Methodology, Investigation, Data curation. Mina Ishimaru: Methodology, Investigation. Atsuko Shimamura: Methodology, Investigation. Helli Kitinoja: Conceptualization, Methodology. Sarah Donnelly: Methodology, Investigation. Jaakko Hallila: Methodology, Investigation. Marika Toivonen: Methodology, Investigation. Camilla Bergman-Kärpijoki: Investigation. Erika Takahashi: Investigation. Wenwei Yu: Methodology, Validation, Supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ide, H., Suwa, S., Akuta, Y. et al. A comparative study to elucidate factors explaining willingness to use home-care robots in Japan, Ireland, and Finland. Sci Rep 14, 27656 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79414-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79414-y